Messi’s left foot. Nadal’s resilience. Going a bit further back, Bolt’s loping stride. Each sporting champion has a variety of skills and attributes but there’s always one that puts them a cut above the rest. In this series, we look at top Indian athletes and identify that one quality that makes them stand out. This week: Rani Rampal’s control over time and space.

What is the X-factor:

Presence. Movement. Time. Awareness.

Call it spatial awareness and you trip over words. Calling it Rani’s space-time continuum on a hockey field sounds like you’re trying to confuse people. The fact is that it involves an instinctive control over three truths – when to move, where to move to and what to do there.

It is like an illusionist’s trick: in the initial melee of the D, she is not to be seen. Blink, and suddenly she is there.

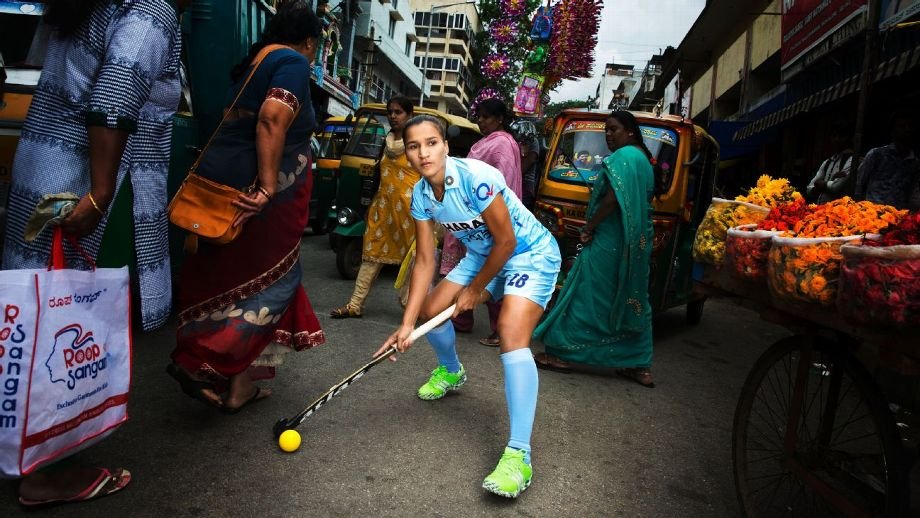

Rani Rampal, captain of India, apparating.

Around her, others are playing international hockey like we know it – top speed, high volume. In Rani Time, in Rani Space (time-space continuum is hard to get away from), everything is in slow, precise steps. In the tiny pocket of space which she arrives into, the ball reaches her. A small step sends the closest defender in the wrong direction, opening up another route for the second, which appears to split into an extra portion for Rani. The stick moves, in either a twitch or a lusty swing, whichever is needed. The rest only see the ball fly past a thicket of legs, bodies, the goalkeeper’s padded limbs and torso, and crack onto the goal board. Or the roof of the net.

Best example: Most recently, the goal that helped India qualify for Tokyo 2020 (now 2021). After wiping out the U.S. on day one with a 5-1 score, the India women froze in the second match, four goals down by half-time, the aggregate scores even. With 11 minutes remaining, in the midst of a goalmouth skirmish, watch what Rani does. At the 3:00-minute mark, she is at the bottom left of the screen, ambling forward. There are nine players ahead of her hurtling around inside the D, diving, stretching, defending, attacking.

Rani intercepts a desperate clearance and takes two steps to trap the ball perfectly. It has turned her around, her back is to the goal. She must have eyes at the back of her head, because two steps to her left, she is perfectly sideways locked onto flight path available. One slap off her stick, and it’s goal. Watch it at high speed and then in slow motion. The nine around her are rendered invisible, irrelevant. It is Rani in her parallel universe operating in her own space-time.

Where it comes from:

By fusing instinct and experience into an amalgam that melts down a sport’s secrets into simple instructions. When. Where. What.

Coach Sjoerd Marijne says it originates from sound technique, perfected through hours of practice, which forms the base layer of Rani’s skill. He gives the example of Roger Federer watching the ball connect with his racket rather than where it ends up. “For him, this is going in slow motion, which is the same as Rani is in the circle. She needs less time than a lot of other players because her technique is so good and that has to do with a lot of repeating in the training and being focused on it.”

Rani was always a child prodigy — India debutant at 14 — but what she has worked towards owning today are not “gifts”, they are her stealth weapons. She says, “I believe so much in training. In focus, concentration, intensity while training. The training that I do before going to a tournament decides what I will do, how I will do in the event.”

It is not merely 100 shots in training, it is 100 perfect shots, “In the match, you will get only one shot. If you frequently do that over and over, it becomes a habit. You don’t have to think, you have to do it.” This is why despite being the slowest on the women’s team’s yo-yo runs, Rani says, “I make sure I touch the line exactly where I should before I get back. If I fall a centimetre short, I know that in a game, I will miss a goal by that one centimetre only.”

Okay, so that’s the nuts and bolts of the precision-striking. Marijne reveals more. The secret sauce, he says, about her physical properties lies in the fact “that she is faster with the ball than without the ball.” With the ball on her stick, she turns into elusive quicksilver with the most minimal feints and dummies, wrong-footing defenders, leaving them behind, earning her extra slices of time.

Marijne says, “With the ball, you see her revive because that’s what she likes the most” — to bring her stick and body skills into play. During a training run, Marijne said he asked the faster players to hustle against Rani, press hard and fast around her, but still she slipped through. Later, she told the bemused Marijne, “She might be faster with the ball, but I am quicker with the thinking.”

Inside the heightened emotion and action in the D, he says it is “more important to be smart in that situation rather than very fast.” In a high-pressure situation, Rani’s mind works at high-speed, issuing clear instructions to her body. “How you do in training,” Rani says, “affects how you do in the match. If you don’t focus hard in training, then in the match, under pressure, you will make more mistakes. Mere saath toh aise hota hai, baaki pata nahin (That’s what I feel happens to me, I don’t know about the rest).”

Those playing alongside Rani have a view from the outside. Forward Navneet Kaur is a year younger than Rani, and like her, belongs to Shahabad-Markanda in Haryana, watching her shoot into the stratosphere of the world game. Rani’s point of distinction, she believes, is her movement on the pitch. In her first national camp in 2012, Navneet watched Rani amazed at how “she would beat defenders so easily.”

On the pitch, Navneet saw a control over tempo. “Rani di is a master at it – she realises her strengths and limitations, knows when to accelerate and when to slow the game down,” she says. It is the striker’s movement – it could be a dart, a dodge, a sprint – that will drag defenders along, freeing up space for others.

The movement may come from training, but Rani’s assists come from skill. Navneet remembers a goal scored in New Zealand earlier in the year, where after a foul on the 25-yard line, she found herself in the striking circle with a defender close by. Rani’s move on the right took the marker’s attention off for a second, Navneet surged forward and the pass came. All she had to do was deflect into goal. “I remember the weight on the pass and the angle. I didn’t have to take an extra touch. It went, first time, with the deflection.” Again, it’s the timing of everything. “She knows when to play the ball, at what angle, at what speed.” It is what creates the inches of advantages, from where moves are born.

Marijne also points to another strength that belongs neither to instinct nor experience — it comes from the core, “Rani has a very strong will to be the best and you can see that with all top athletes. Will power is one of the most important characteristics to be truly great.”

But what about the apparating? How is that done?

Former India captain Viren Rasquinha’s job as defensive centre-half was to mark the players with Rani’s mesmeric qualities — like Jamie Dwyer and Teun De Nooijer — and play alongside and support his own maverick teammate, Dhanraj Pillay. “The great forwards like Rani always have the quality to understand where there is space, where they will be, and to go there exactly at the right time. Their sense of positioning on the field is perfect. So they don’t score spectacular goals but they always seem to score goals. The ball eventually finds the way to them. When you mark such players, everyone tells you that this will happen and yet you can’t stop it.”

Along with understanding the geometry and physics of the game, players like Rani have also learnt, Rasquinha says, to almost mind-read. “They know the psychology of defenders – they know what they are thinking and they are thinking one step ahead.”

Because it’s happened before, because they’ve been there, because like Rani, they’ve practiced it so often that it’s written into the motherboard of their muscle memory. “One moment they are with you, like Dhanraj, you think you are marking him, and the next moment, he is 3-4m away, just out of the reach of your stick.”

Rani has spent a decade in the game, her teenage energy beaten down by numerous injuries. These days, she is holding her body together on ambition and athletic tape, but during this time, her game intelligence, awareness and anticipation has only grown exponentially. “This is talent but also years of training,” says Marijne. “So she knows exactly what to do in which situation in and around the circle.”

It is the striker’s instinct, Navneet says, which involves reading patterns, which after decades, becomes like driving, reflexive. Not thought, but action. In Rani’s case, it also involves distancing the event, the match, the score, the prospect from the moment at hand and use that detachment, to bring down the hammer and drive the nail into the opposition’s dream.

In his 2006 movie The Prestige, Christopher Nolan told us that every magic trick has three parts – the pledge, the turn and its toughest act, the prestige. In the Rani repertoire, the prestige lies in the finishing, in its calm inevitability.

Rasquinha says, “This is hockey, you get only a split second. A second longer, the defender will close you down.” A normal high-quality international player’s reaction is more natural, “If you get the ball in the same position, you start fretting, you’re in a hurry.” Not players like Rani. He asks us to be grateful. “Players of that caliber don’t come out every day. All those who play for their country are very good players. But the players who transcend the game are very, very few.”

What I like about it:

Being humble witnesses of sporting genius by sighting its everyday, jaw-dropping wizardry. Through this young Indian woman whose fragile form, in an instant, can generate the impact of a megaton wrecking ball.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.